© Aidan Ragan via Midjourney/Aidan Ragan via Midjourney Left: Image of AI programs such as Midjourney 4 used to create muscular or incomplete arms. The right hand made with Midjourney version 5 is much more realistic.

© Aidan Ragan via Midjourney/Aidan Ragan via Midjourney Left: Image of AI programs such as Midjourney 4 used to create muscular or incomplete arms. The right hand made with Midjourney version 5 is much more realistic.

When Aidan Ragan creates artificially rendered images, he expects the people in his photos to have wrinkled hands with blood vessels and five or more fingers. But this month, while taking an art class at the University of Florida, he was amazed to see the famous sculptor draw living hands.

"It was unbelievable," Ragan, 19, told the Washington Post. “That was the only thing holding him back and now he is better. It was quite scary … and exciting."

AI image generators that create images based on written instructions are rapidly gaining popularity and productivity. People inputted all kinds of suggestions, from the mundane (drawing Santa Claus) to the absurd (a stained glass-style dachshund in outer space), and the program produced images that looked like professional paintings or photo realistics.

However, the technology has a major drawback: it creates a realistic human hand. The datasets that train the AI often capture only parts of the hand. This often results in photos of an outstretched hand with too many fingers or an outstretched wrist, a clear sign that the AI-generated image is fake.

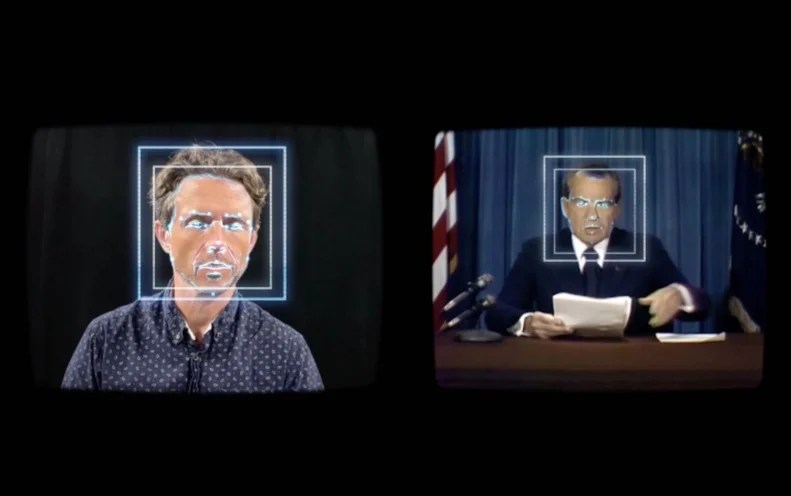

But in mid-March, Midjourney, a popular image maker, released a software update that appeared to fix the problem, and artists reported that the tool produced perfect hand-drawn drawings. That fix came with a major problem: This week, the company's upgraded software was used to create a fake image of arrested former president Donald Trump that looked real and went viral, demonstrating the disruptive power of technology.

© Aidan Ragan/Midjourney AI-generated hand-drawn using an older version of Midjourney, a popular AI-based imaging tool.

© Aidan Ragan/Midjourney AI-generated hand-drawn using an older version of Midjourney, a popular AI-based imaging tool.  © Aidan Ragan/Midjourney AI generates hand drawings using the latest version of Midjourney.

© Aidan Ragan/Midjourney AI generates hand drawings using the latest version of Midjourney.

This seemingly innocuous update is a boon for graphic designers who rely on AI rendering for realistic art. But it has sparked a lot of controversy about the dangers of artificial content being indistinguishable from real images. Some say this hyper-realistic AI will put artists out of work. Others argue that flawless images will make deepfake campaigns more credible, since there is no clear sign that the images are fake.

"Before you get into all those details, the average person … will say, 'OK, seven fingers here or three fingers there, that's probably fake,'" said Hani Farid, a professor of digital forensics at the University of California. , Berkeley. California at Berkeley. . "But as he starts to grasp all the details … those visual cues become less reliable."

Text to image maker

The past year has seen an explosion of text-to-image generators amid the significant growth of generative artificial intelligence, which provides software that creates text, images or sounds based on data you provide.

Created by OpenAI and named after artist Salvador Dali and Disney Pixar's WALL-E, the popular Dall-E 2 took the internet by storm when it launched last July. In August, startup Stable Diffusion released its own version of what is essentially anti-DALL-E, with fewer restrictions on how it can be used. The Midjourney Research Lab launched its version over the summer, creating the painting that sparked controversy in August when it won an art contest at the Colorado State Fair.

© Mikayla Whitmore for The Washington Post Jason Allen works in his room at the Westgate Hotel in Las Vegas on Sept. 2.

© Mikayla Whitmore for The Washington Post Jason Allen works in his room at the Westgate Hotel in Las Vegas on Sept. 2.

This picture maker works by taking billions of pictures taken from the internet and recognizing the patterns in the photos and the accompanying text words. For example, the program learns that when someone types "bunny", it associates a picture of a furry animal and sends it back.

But remaking hands remains a thorny problem for software, said Amelia Winger-Bearskin, an assistant professor of artificial intelligence and arts at the University of Florida.

Why are AI image generators bad at drawing hands

According to him, software created by artificial intelligence cannot fully understand what the word "hand" means, making it difficult to visualize body parts. Hands come in all shapes, sizes and forms, he says, and the images in the training data set are often more focused on the face. When hands are depicted, they are often folded or moved, indicating a change in the appearance of a body part.

"If every picture of a person were like this," he said, spreading his arms wide during a Zoom video interview, "we could reproduce hands pretty well."

According to Winger-Bear, the Midjourney software update released this month appears to have fixed the problem, though he notes that it's not perfect. "We still have a lot of freaks," he said. Midjourney did not respond to requests for comment to learn more about the software update.

Winger-Bearskin says Midjourney may have improved its image dataset by tagging photos where hands weren't hidden as a higher priority for training the algorithm and photos where hands were blocked as lower priority.

Julia Wieland, a 31-year-old German graphic designer, says she really likes Midjourney's ability to create more realistic hands. Wieland uses the software to create mood boards and layouts for visual marketing campaigns. In his opinion, correcting human hands in post-production is often the most time-consuming part of his job.

© Julie Wieland/Midjourney AI created this image of an elderly man playing the piano in an old version of Midjourney.

© Julie Wieland/Midjourney AI created this image of an elderly man playing the piano in an old version of Midjourney.  © Julie Wieland/Midjourney AI generated the image using the latest version of Midjourney.

© Julie Wieland/Midjourney AI generated the image using the latest version of Midjourney.

But the update was bittersweet, he said. Wieland often enjoys tweaking AI-generated images or tweaking images to suit his chosen creative aesthetic, heavily inspired by the lighting, glare, and window frames famous in Wong Kar's My Blueberry whoa. . Evening

"I miss looking less than perfect," he said. "While I love getting beautiful shots straight out of Midjourney, my favorite part is the post-processing."

Ragan, who plans to pursue a career in artificial intelligence, also says these perfect images take away from the fun and creativity involved in creating AI images. "I really enjoy the artistic aspect of interpretation," he says. "Now it seems more difficult. It's more like a robot… more like a tool."

Farid, of the University of California, Berkeley, said Midjourney's ability to create a better image poses a political risk because it can create an image that appears more credible and provokes public outrage. He pointed to a picture Midjourney drew last week that seemed plausible of Trump's arrest, even though it wasn't. Fareed noted that small details such as the length of Trump's tie and hands have been improved, making him more believable.

"It's easy to get people to believe that," he said. "And then when there's no visual [error], now it's easier."

Until a few weeks ago, said Farid, rival detection was a reliable way to determine whether an image was fake. According to him, it is increasingly difficult to do considering the increase in quality. But the clues are still there, he says, often in the background of a photo, like a crushed tree branch.

Farid said AI companies need to think more broadly about the damage they can do when improving their technology. He said they could include a fence that would not allow playing certain words (which the Dall E-2 said he had), include watermarks on images, and prevent anonymous accounts from taking photos.

But according to Farid, artificial intelligence companies are unlikely to slow down the improvement of their image generators.

“There is a constant arms race in generative artificial intelligence,” he said. "Everyone wants to know how to make money, and they move fast, and security slows things down."